[Scene 1: West Village, New York City, 1975. A legendary songwriter, mid-30s, is surveying the neighborhood where he cut his teeth a decade before. A violinist, younger and without his star status, but striking, with long dark hair and mysterious poise, enters stage right.]

The passerby was Scarlet Rivera, a previously unknown musician whose hypnotic violin became the signature sound of Bob Dylan’s newly minted touring group, the Rolling Thunder Revue, and his gestational new album, Desire. Naturally, Dylan—world historic genius, generational icon, and general weirdo—pulled over his car, resolved to ask her just exactly what her deal was. For an artist so concerned with myth, this chance encounter must have been irresistible. Was she phantom, muse, or curse? Was she really named Scarlet Rivera? “I meet witchy women. I wish they’d leave me alone,” he told Jonathan Cott, in a 1978 Rolling Stone interview, not stopping to consider the possibility that the feeling was mutual. Not long after the album came out, she vanished from his life and the public eye.

As with so much Dylan lore—from the fabled teenage eye contact with Buddy Holly to the arrest in Springsteen’s childhood neighborhood—it seems too unlikely to be true, and too preposterously random to invent. It’s of a piece with the world of Desire, where what’s real and what’s weird are largely indistinguishable.

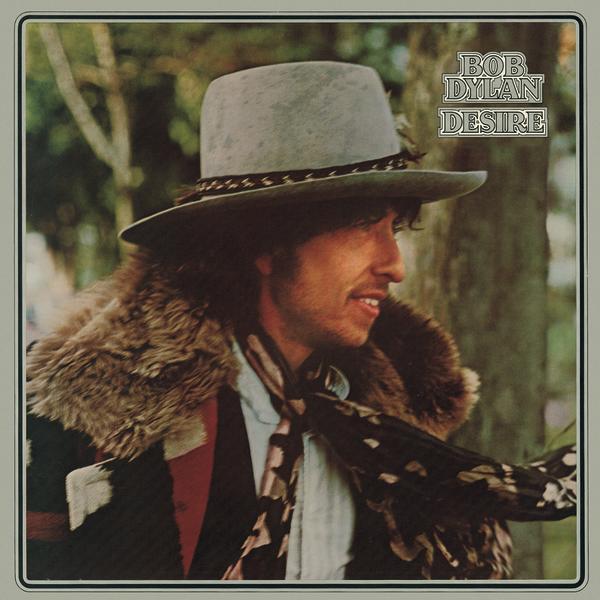

Dylan’s previous record, the precision-controlled display of omniscient superego that was 1975’s Blood on the Tracks, had set an impossibly high standard for its follow-up. In response, Desire was a fantasia of grave injustices and grave robberies, exotic and dangerous locales, broiling days and fleeting gestures in the face of grim destiny. Its nine songs spread out over 56 minutes, co-mingling protest folk, travelogue tunes, throwback country, and sideways klezmer, all comprising one peculiar episode in the baffling sweep of his career. Blood on the Tracks was a document of personal and romantic trauma that traced an outline around a generation who prized individual freedoms to the point of self-annihilating alienation. Desire is about getting stoned and strange and trying to forget about all of that.

Desire is not a subtle album, and it does not commence on a subtle note. “Hurricane”—an audacious eight-and-a-half minute recounting of the 1966 arrest and conviction of the middleweight boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter on charges of triple homicide—begins with the interweaving and insinuating strains of Dylan’s acoustic guitar and Rivera’s violin. One of seven songs on Desire co-authored with the playwright Jacques Levy, it employs stage directions to set its scenery: “Pistol shots ring out in the barroom night/Enter Patty Valentine from the upper hall.” Intentional or not, the effect of the dramaturgy is to suggest a not-strictly-speaking-literal recounting of events, introducing the queasy sensation that we are being carried along by storytellers whose commitment to the facts is secondary to their impulse to thrill and desperation to deliver a higher truth.