For all the chaos in his music—and despite his famously combative reputation—Lou Reed was a dedicated practitioner of yoga, meditation, and martial arts. He began studying tai chi as part of an effort to get off speed and booze and strengthen his wrecked body as the 1970s drew to a close. An early teacher recalls Reed’s hands shaking so hard he could barely hold the positions, but he stuck with it. When he toured, he brought along his swords and instructional VHS tapes, practicing in hotel gyms and conference rooms; upon returning home he was known to take the taxi straight from the airport to class. In the final six years of his life, he intensified his focus, doing six days of tai chi followed by one day of yoga, week in and week out. Laurie Anderson, his partner of 21 years, said he was “looking for magic.” He was doing breathwork when he died, in fact—eyes wide open and hands in a tai chi position, with Anderson’s arms around him.

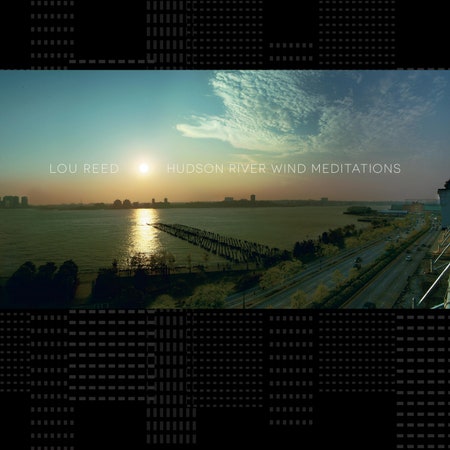

Newly remastered and reissued with extensive liner notes by Light in the Attic, Hudson River Wind Meditations was first released in 2007, on a small Louisville, Colorado, label specializing in self-help and spirituality. But in the beginning, it wasn’t meant for public consumption at all. According to Anderson, Reed made early versions of these pieces to accompany guided meditations recited by Shelley Peng, an herbalist and acupuncturist. The music eventually morphed into a soundtrack for his tai chi practice, although not all his classmates were on board. Some fellow students preferred the traditional Chinese music that their teacher, Master Ren GuangYi, typically played, and asked for Reed’s tape to be turned off. One student walked out the door and never came back. (Reed’s drone music always did have a polarizing effect on listeners.)

But Reed and Ren kept playing the tape, and according to Anderson, anyway, some of his classmates eventually came around, saying that it was the best tai chi music they’d ever heard. One wonders to what extent Reed’s fame—or perhaps simply his legendary stubbornness—greased the wheels. In an amusing anecdote in the liner notes, yoga instructor Eddie Stern says that when he worked with Reed, “Whether we were doing yoga or meditating, the Hudson River Wind Meditations came on, and even though I am a silent meditator and don’t normally recommend listening to music when meditating, I would let it slide for Lou.”